School Safety Expert on Negligent Supervision and School Injury Liability

School negligence cases involving teachers, coaches, camp counselors, bus drivers, and other personnel resulting in injury to a child are ever-present in the news. Negligence in schools that results in sexual abuse, death, and sports injury all present opportunities for costly negligence claims that may entail large settlements or grave jury verdicts.

What is a Negligence Claim?

School negligence claims are legal actions families and legal teams pursue to recover for injuries, deaths, or other damages suffered by a student or the student’s family due to administrators’ and personnel’s failure to act with reasonable care to prevent foreseeable risks. Such claims hold schools liable for carelessness rather than international harm.

Negligence examples in schools that can lead to a child’s harm include negligent supervision during sports, failure to properly and frequently maintain school premises and playground equipment, lack of sports safety gear, in the school bus, on field trips, or during other school activities on and off campus, unmonitored or unrestricted staff-child interaction, lack of robust school policies for incident prevention, reporting, and response, unaddressed incidents of harassment, bullying, and intimidation (HIB), discrimination, and other breaches of the professional standard of care.

Plaintiff and defendant attorneys can follow a few recommended steps to determine the merit of filing a complaint and the strength of a defense. In this article, a school safety expert presents a systematic process to guide attorneys in assessing school injury liability arising from negligent supervision by a school or agency employee.

Professional Standard of Care

Schools and other agencies that supervise children are held to a high standard to protect children’s health, safety, and well-being. A reasonable school administrator or teacher/supervisor standard is applied when assessing school negligence cases. This standard compares how another person of the same education, training, and experience would respond in the same circumstance. This goes beyond the typical “reasonable person” standard and requires an assessment based on the professional standard of care in the field of child education, supervision, and safety.

When a child is injured, dies, is assaulted, or is sexually abused, often the outcome is a negligent supervision lawsuit on the part of the involved staff member. The court might find the school or youth-serving agency liable for a tort if the employee breached a professional duty that was a proximate cause of the child or student’s injury. If, on the other hand, the school or agency, through its employee, acted reasonably under the circumstances and within the professional standard of care, the defense is likely to prevail.

School-Related Injuries and Negligence Examples

Because nearly 80 million children in the United States and Canada spend a significant portion of their waking hours in school, the potential for school injury liability due to negligent supervision, poor planning, insufficient staff training, ineffective policies, and poorly maintained premises is extensive. Public perception, however, often distorts both the extent of school liability and the nature of injuries sustained by students during school-related activities.

Public attention on student injuries tends to focus on school violence, mainly because it dominates media coverage. However, the vast majority of student injuries occur in situations that may initially appear unintentional or accidental but, in many cases, can be traced back to failures in supervision, activity planning, staff training, facility maintenance, or negligence in schools. Studies indicate that school-aged children are nine times more likely to sustain an injury linked to negligent supervision or environmental hazards than to be the victim of an intentional act of violence at school (ResearchGate, 2018).

Each year, children in the United States under the age of fifteen sustain more than 14 million unintentional injuries, with an estimated 10 to 25 percent of these occurring in and around schools (CDC, 2022). In total, 1 in 14 students suffers a medically attended or temporarily disabling injury while at school (ResearchGate, 2018).

In elementary schools, playground injuries are most common and often occur due to poorly maintained equipment, inadequate safety surfacing, or negligent supervision. According to the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, over 200,000 children aged 14 and younger receive emergency treatment for playground-related injuries each year, with 46% of these injuries occurring in schools (CPSC, 2022).

In secondary schools, a significant number of injuries result from athletic activities, including physical education classes and organized sports, where the risk increases when schools fail to implement appropriate safety protocols, ensure proper training, or enforce policies that protect students from preventable harm. Sports and recreational activities account for 55% of school-related injuries (ResearchGate, 2018).

While many injuries in school settings are classified as unintentional, several preventable factors contribute to their occurrence:

- Negligent Supervision: Lapses in monitoring students, particularly in high-risk areas such as playgrounds, gymnasiums, and science labs, can lead to avoidable accidents and school negligence cases.

- Poor Maintenance: Unsafe conditions, such as damaged playground structures, unsecured sports equipment, or hazardous flooring, significantly increase injury risks.

- Insufficient Training: A lack of proper training for teachers and staff in emergency response and safety procedures can result in mishandling of injury situations.

- Ineffective Policies: The absence of, or failure to enforce, safety policies may create conditions in which preventable injuries occur.

Improving student supervision, ensuring regular maintenance, providing comprehensive staff training, and implementing effective policies can significantly reduce negligence in schools and mitigate school injury liability risks.

The Extent of School Liability in Negligent Supervision Cases

So, what is a negligence claim likely to result in?

Zirkel and Clark (2008) analyzed the trends in the frequency and outcomes of published decisions of student-initiated negligence claims in K–12 public schools in the United States. In each of these negligence cases, schools and/or personnel were named as defendants. The researchers analyzed a representative sample of 212 published decisions involving personal injuries to students over 15 years from 1990 to 2005.

The sample included only student claims of simple negligence and excluded claims alleging gross negligence, intentional torts, and educational malpractice. The data sources were the Sports and Torts sections of the Education Law Yearbook (ELA 1991–2006). The authors selected every fourth case within these boundaries to develop their sample.

In almost two-thirds of the negligent supervision cases in this sample, the school successfully defended itself conclusively. The plaintiff won conclusively in less than one-tenth of them.

The 212 decisions spanned 40 states, with the most significant number in New York (n=66). On a per-capita basis, New York again led the nation, with 23 decisions per 1 million students. Among the 24 decisions (11%) in which student plaintiffs won conclusively or otherwise were awarded damages, Louisiana recorded the most (n=9), while New York (n=3) was the only other jurisdiction with more than one decision in the student’s favor. Louisiana, therefore, had the highest rate of decisions against schools, with students winning damages in 9 of the 14 cases during the study period (64%).

Among the various bases for decisions in this study, government and official immunity was the most prominent factor (46 percent) in school-favorable outcomes. The plaintiff’s failure to prove breach of duty, one of the elements of negligence in schools discussed below, was the critical factor in 41 percent of negligent supervision cases decided in favor of school districts.

Secondary schools accounted for a notably higher frequency of published negligence decisions, with a ratio of more than 2-to-1. The authors attributed this to several factors that typically distinguish high schools from elementary schools: the greater availability of risky, specialized activities; a higher proportion of students prone to violence; and generally larger student bodies. Primary schools accounted for a significantly higher proportion of conclusive decisions in the plaintiff-students’ favor (16% vs. 7% for secondary school students). In large part, the authors note, this is likely because younger students are considered more vulnerable, which places a higher duty of care on the school and contributes to a lower incidence of contributory negligence claims.

Among school negligence cases that were either decided conclusively in favor of student plaintiffs or where students were awarded damages, the most frequently blamed individuals for negligent supervision were coaches (n=5). Teachers were found negligent in only two decisions, and in both cases, they were not personally liable. Other decisions were attributable to various examples of negligence in schools, including, transit-related activity (n=12), defined as the student riding on a school bus, walking to or from a bus, or walking between home and school; negligence in maintaining the premises (n=3); supervisory failure to prevent a student-teacher sexual relationship (n=1); and student bullying (n=1).

The key findings of this analysis, that the frequency of published decisions remained stable and that schools won the large majority of negligence cases, are contrary to the general perception that negligent supervision is a significant and increasing source of liability. In fact, it is neither. Several factors, including campaigns by political lobbying organizations and the liability insurance industry, fuel this perception. It is also fed by the news media, which report on a handful of high-profile cases showcasing emotionally charged people. In truth, most school negligence cases similar to those reported by the media never make it to a courtroom. It should be noted, however, that in the small sample of negligent supervision cases in which students won conclusively or received partial damages, the average known award was significant, $430,000.[1]

These findings illustrate the importance of attorneys understanding what juries look for when determining a school injury liability. Let us review the elements of tort law as it applies to school liability.

Elements of Tort Law and School Liability

Tort law provides a framework for determining liability in negligence in schools. Tort claims in the context of schools and agencies are based on the premise that an employee is liable for the consequences of his or her conduct if it results in child injury. The majority of child injury lawsuits involve claims of negligent supervision.

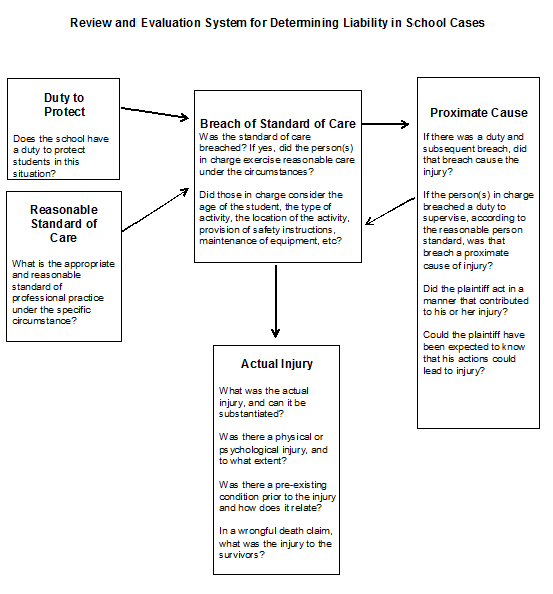

State and provincial laws govern tort claims, but when it comes to the question of what is a negligence claim, each of the following elements must be assessed by both plaintiff and defendant attorneys: duty to protect, failure to exercise a reasonable standard of care, proximate cause, and actual injury.

Plaintiff and defendant attorneys should consider the following questions when assessing school injury liability:

- Did the school or agency have a duty to protect the child in the particular situation?

- What was the reasonable standard of care under the circumstances, and did the school or agency apply that standard?

- If there was a breach of the standard, was it a significant factor in causing the injury?

- Did the party contribute to the injury through their negligence?

- Were there any intervening variables that may have interrupted the proximate cause or causation of injury?

- Was there a substantiated injury?

Let us now break down each of these elements of tort law as they relate to negligent supervision cases:

Duty to Protect

Examples of negligence in schools include failing to address obvious risks. School and program administrators and child supervisors have a responsibility to anticipate potential and foreseeable dangers and take reasonable precautions to protect students from injury.

With respect to activities that take place during the school or agency program, the duty to protect is usually easy to prove. In addition to the school day and on-school-grounds activities, courts have held that this duty may apply beyond school hours and when off school grounds. For instance, the school may have a duty to protect children on a school-owned or contracted school bus. A teacher or aide may have a duty to protect a student from wandering off during a class trip. A teacher may have a duty to protect a student whom he drives home from football practice on Saturday morning.

Failure to Exercise a Reasonable Standard of Care

Breaches of the professional standard of care constitute negligence examples in schools. If a school or agency employee fails to take reasonable steps to protect a child or student from injury, the employee can be found liable for negligent supervision. Courts will weigh an employee’s actions against what a reasonable employee would have done in a similar situation.

For instance, would a reasonable teacher hand a pair of sharp scissors to a third-grader and ask her to scrape hardened clay from a wall while standing on a ladder? Would a reasonable custodian fail to repair a latch on the cafeteria wall that holds a 300-pound table in place? What precautions or level of supervision should the school or agency consider to protect children from injury in these situations?

In negligent supervision cases, the degree of care exercised by a reasonable administrator, teacher, bus driver, or other employee of a school or agency is determined by considering:

- Operational policies and procedures of the school or district;

- The employee’s training and experience;

- The age and capacity of the child and whether appropriate supervision was provided;

- The type and appropriateness of activity, and, if necessary, was the child trained and warned of dangers;

- Whether the supervising employee was present; an;

- The environment in which the injury occurred.

An elementary school student and a child in a preschool-age daycare center will typically require more supervision than a high school student when playing on the playground or on a class trip. Also, students in a physical education class will require closer supervision than those who are reading quietly in the library.

A child’s disability, if one is present, presents an additional layer to the definition of a reasonable standard of care that must be considered in school negligence cases. A child with a known behavioral disability, for instance, may require closer supervision on the playground. In many negligent supervision litigations, courts have held that several factors, such as a student’s disability and unique needs, are relevant in determining a reasonable level of supervision in certain situations.

Proximate Cause

Another critical question to consider in assessing the merit of negligence claims is whether the school or agency employee failed to exercise a reasonable standard of care, and if so, did it place the child in harm’s way and result in injury?

The ability to prove this element, called proximate cause in the United States (or causation in Canada and remoteness in the United Kingdom), depends on establishing that a child’s injury could have been foreseen and prevented. If the child or student injury could have been anticipated and prevented by an employee’s exercise of a reasonable standard of care, legal causation may exist, and could prove negligence in school.

However, the question is whether the injury was a natural and probable result of the school’s or employee’s wrongful act, and whether it should have been foreseen and could have been prevented in light of the circumstances. A wrongful act could be described as negligent supervision, for instance, or as a deliberate action, such as sending a student off campus for a non-educational reason, however well-intentioned, that leads to an injury. Let us look at a negligence example involving a deliberate action.

A woodshop teacher replaced a broken bolt for a protective device on a table saw with a bolt he found in a desk drawer. The teacher knew that the bolt did not meet the manufacturer’s specifications but decided to use it anyway. Three days later, the device came loose, and a student nearly severed three fingers while using the saw. In a school negligence case, the jury could determine that the teacher’s decision to use the nonstandard bolt was a deliberate action and the proximate cause of the student’s injury.

A negligent supervision claim may not be successful if the injury could not have been prevented, even when reasonable care is exercised. The inevitability of an accident nullifies the proximate cause. This may hinge in part on whether the child contributed to their injury. Let us return to the woodshop and the table saw.

Another teacher provided clear instructions on how to use the saw, administered a paper-and-pencil test to each student, and individually observed and instructed each student while at the saw. Students were provided with safety rules and warned about the dangers of using the saw improperly. The saw was regularly inspected and taken out of service if it needed repair. A student disregarded the instructions and warnings, misused the saw, and was injured. Is the school liable for the student’s injury? Did the student contribute to his injury?

Contributory Negligence

Other examples of negligence in schools include instances in which a child’s actions, such as ignorance of safety guidelines or careless behavior, contribute to their injury. If it can be established during negligent supervision litigation that a child contributed to the injury, the school or agency may assert contributory negligence, a common defense against school injury liability. If the court holds that contributory negligence was a factor in the child or student’s injury, the school or agency may be held only partially liable or not liable at all, depending on the jurisdiction.

In school negligence cases, it is challenging to prove contributory negligence against children under the age of seven because tort law generally holds that young children are incapable of contributing to their own injuries. If, for instance, a pothole in the playground blacktop is marked off with orange cones, contributory negligence may not be a factor if a young child walks through the cones, trips in the pothole, and breaks an ankle. Even with adequate barriers and warnings on the playground, a young child may not be expected to understand the danger and protect their own safety. A child may be able to collect damages even if she contributed to her own injury.

Actual Injury

The presence of an actual injury is the final element that must be proven in a negligent supervision case involving a school or agency. The injury does not have to be physical; it can be emotional, but it must be documented and sustainable. Without a provable injury, damage claims will not be successful, even when negligence is involved.

SUMMARY

The extent of claims related to school negligence has remained relatively constant for more than two decades. Published decisions in simple school negligence cases have overwhelmingly favored school district defendants. A large proportion of these decisions have hinged on government and official immunity and on plaintiffs’ failure to prove breach of duty.

Courts have examined the key elements of negligence in the context of schools and agencies responsible for children’s health, safety, and well-being, as well as the reasonable professional standard of care. It is important for both attorneys who seek to bring a case against a school or agency and those who defend schools and agencies to have a system to determine the extent of a school’s injury liability.

Expert Witness Services in Negligent Supervision and School Liability Cases

At School Liability Expert Group, having worked with parents, schools, other child-and-youth-oriented agencies, and hundreds of law firms across the United States in agency and school negligence cases, we are well-versed in the numerous examples of negligence in schools that can result in student injury.

We can therefore help schools escape these pitfalls through thorough program reviews and recommendations for improvement.

Plaintiff and defendant attorneys can count on us for prompt, reliable, and comprehensive expert witness services and consultations in various school liability cases.

Book a call with our education expert witness team today for assistance with a negligent supervision case.

[1] Zirkel, P.A. and Clark, J.H. “School Negligence Case Law Trends.” S.Ill Univ Law J. 2008:32; 345-363.

Miss Kim Alston

My son had a accident at school on 4th April 2014 at school he fell and broke his left wrist /arm ,while he was in medical office no one out of three first aiders asked if he needs his inhalers has he’s asthmatic and all inhalers are kept in school so no excuse,also no ambulance was called . I don’t drive which I did tell the school head teacher and teacher s I think I was expected to get I a bus with my son with all his bags and coat and a broken arm ,when we got to hospital my son badly broken 2 bones in his arm /wrist he had first operation the next day to put wires in we were kept in a few days then on the 7th April we went to the fracture clinic to have X-rays to be told to come back next day my son had to have a second operation and have a plate put in his arm,he’s had that done .Not happy has it says I the school s policy if a child has a serious accident then the emergency sevice is to be called ,if they were my son would have been given some sort of pain killer and a nebuliser for his asthma . The school is Firs Farm Primary .

veronica

To days ago …i was wating for my son at the bus stop he just turn 5 he is on kindergarten. ..20 mins ppassed from the time the bus was supposed to be there but never showed up…..me thinking the bus was late also around 15 more parents on the same stop waiting. ..them we saw. A crowd of kids walking towards us…my heart went dead for a few mins my son was all the way back behind almost to blocks away crying and shaking he said the bus driver yelled at them to get offf even doe the childrens to them it was not there stop he did not listen to them ..he lest the about 2 light up about a 20 min walk from their bus-stop,…,my son cross a principal street and 2 others following other kids he was so scared. …how can my son have been left at the wrong stop even doe he said it wasnot his stop??? A hit could have hit him!! Or stolen or worse thank god he is okk …but what if????? …..,,the school said they are sorry and investigating the case thats all they say but no is not enough actions have to be taken…what can i do???? Do i have a case so it would never happen again..thank you!!

Dr. Edward F. Dragan

Hello there,

We recommend that you follow-up with the school principal and if there is no action and this happens again, you should notify the Superintendent and the Board of Education. Thank you for your comment and we hope this helps!

Best regards,

Education Management Consulting Team

Mary Ivey

While in the locker room at school my son was hit from behind by a student. He was dazed but looked to see who hit him. Lost his balance and his head hit the concrete and caused concussion/cracked skull. He was knocked unconscious. While unconscious and bleeding this boy the jumped on him and brutally beat him. His eye and face was black. His jaw was swollen. His lip was swollen he was even beaten in the head around the crack which was bleeding. The school suspended both boys three days and have tried to hide the truth. They in so many words told me that my son deserved it. They would never discuss beating while unconscious. It is football season. I think that is why. My son will not return. They did not call 911 and no matter how hard I tried to defend my son brutal a

ttack they woukd not discuss it nor drop the suspension which was to sidetrack me to cover up no adult supervision. Since they treated my son so badly he will not return to the school. His life has been turned upside down and they will not apologize. They will not speak of the truth. It was a horrific scene. A friend of my sons came over and told me that the boy that hit my son and my son was laughing. That my son was hit from behind lost his balance and when his head hit the floor he thought that he was dead. He said he then saw the boy beat him up with his eyes were shut. He said that he had to look at my sons blood on his shoes all day. He said that even though the coaches were outside the door he was scared. No one got help. My son had staples put In his head afterwards. And remained bruised still after 8 days. He said that he will not go back to school because he knows right from wrong and said that they did nothing but try to get him to say stuff when he was bleeding and did not treat him right. His last year with his brother is a senior will not happen and his baseball career with the school is gone because he will not return. Both are 14 ninth grade. Why is the school trying so hard to cover this up?

Dr. Edward F. Dragan

You should check the school’s anti-bullying policy and follow it to make a formal complaint. Once it is placed in the format of the school policy the school has an obligation to appropriately investigate and take action, if they determine that the behavior of the other students was, in fact harassment, intimidation or bullying. To say that it might have been “horsing around” is not an appropriate response. “Horsing around” can cause injury and there is a fine line between this and acting to intentionally harm another. The school has a student code of conduct that should cover discipline of students for “horsing around” and other inappropriate behavior. However, if left in this context, the school can determine that the behavior doesn’t warrant discipline and you may not be able to do much to change their mind. You also have the option of reporting the behavior to the police who will consider it as possible assault and battery. If they do conclude that it was, then criminal charges might follow. We hope this helps. Best regards, Education Management Consulting Team.

Laura

What happened to your son is a crime and should have been reported to the police. The other student assaulted him, and it sounds like your son could have died. For the safety of others, please report this.

I would also consult a lawyer to take action against the school district for negligence. Why you are waiting for the school district to admit they were wrong makes no sense to me. They have to protect themselves from liability, and it’s your job to find them liable. That’s just the way it is. Good luck and I hope your son is feeling better.

Mary Ivey

Superintendent, school resource officer or principal will not discuss this. They will only say things like this happen when kids are in the locker room hoarseplaying. Anything to blame my child. Which three kids said he did not touch the

other boy.They act like this is nothing yet my sons life he knew is over. I am having panic attacks because I scared that if this can happen there is no justice in the school system if it the people who are suppose to care dont punish the child who did wrong.

Mary Ivey

Also the school after acted like they were in a war with ne when all I wanted was an apology and for that other boy to be expelled. The reason he stopped beating my son was because his hand broke.

Araceli Quiroz

My son broke his left leg at school by a soccer post. He says that a kid got stuck in the net of the soccer post and then the kid got free but the soccer post fell down and the soccer post fell on my son’s ankle. The school nurse took my son to her office but she didn’t call the ambulance. His left leg look really bad and had lots of pain. The principal says to my husband that accident had never happen, I think she’s right how a soccer post fall is not suppoce that has to be secure,what about if the soccer post fall in his back or head or if more kids were affects.please can you respond,what can we do?

Dr. Edward F. Dragan

Thank you for your comment. You should seek help of an attorney. Once you have an attorney you can have him contact me to assist with your case. Best regards, Education Management Consulting, LLC Team.

Jenny

Early Februray I was doing a school activity in debate. A metal blade was sticking up from the floor, which the teacher put in mutliple request to get fixed, sliced the side of my foot and when I had to go to the front office and get it cleaned up thats when they sent people to go in the class and fix it. ( Probably to hide the evidence) is this a possible negligence case?

Dr. Edward F. Dragan

Jenny,

Thank you for your comment. If your injury had been significant causing permanent and significant loss, the Shool’s failure to respond and correct the problem could have been considered negligent.

Anna minchaca

Hello my son was at school on 12 15 2015he was at p.e. n on the field n they were playing n his foot got stuck in a golfer hole n now he has a broken ankle n they let him walk home like that n I was not notified about his injury when it happened at school n now what do I do please help me n him

Dr. Edward F. Dragan

Thank you for your comment. I suggest that you seek advice from a personal injury attorney, and he will advise whether using an education expert witness would be needed. I hope your son is OK. Best regards, Education Management Consulting, LLC Team

Dr. Edward F. Dragan

Thank you for your comment. You should seek help of an attorney to evaluate if there is anything that you can do. I hope your son is doing better now. Best regards, EDMGT Team.